The loss of Paul Gottlieb on June 5, 2002 at age 67, it was a serious blow to the art lovers of the world. His era with HARRY N. ABRAMS contained a long list of accomplishments and he alone was most responsible for developing their reputation for beautiful art books. Some of the last books during his tenure included Joseph Cornell, Ann Hamilton, Janet Fish and Phillip Pearlstein, the remarkable figurative painter. Gottlieb saw the value of creating and promoting art books as catalogues in conjunction with gallery or museum shows. ABRAMS book about Andrew Wyeth’s “Helga Series” of portraits sold over 500,000 copies after it was published in 1987. It was a highlight of his career.

One final note about Paul Gottlieb. He was a friend to artists and writers. In April of 2002, he was named executive director of APERATURE, publisher of photographic monographs. He became chairman of the Academy of American Poets, and he was a member of the board of MOMA for many years. Carol Brevant, in her internet article about Paul for “A Footprint We Leave Behind” quoted him…”My observation is that most people who succeed at anything encounter adversity of some kind and learn to transcend it.” And about art, he observed: “Art is one of the few continuums of the human experience; when you look at all civilizations, each produces art; it’s a kind of footprint we leave behind.”

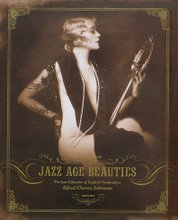

A week or so later I got an email from Senior Editor Christopher Sweet. He mentioned that Eric Himmel had passed my material on to him. He was very excited about my proposal and said he would like to talk to me about publishing a book on Alfred Cheney Johnston. The last line of his email read “And, I want to purchase one of Johnston’s photographs!” I was not surprised Johnston had found another fan.

Christopher Sweet specialized in books on photographers…Especially books on “lost” photographers. I could tell right away that he had “a good eye.” I had sent him a number of copies of Johnston’s photographs, and he earmarked one photo in particular for its stunning artistry- a semi-nude of Norma Shearer. We both agreed that it was remarkable in its beauty and composition. Sweet, an artist himself, clearly responded to Johnston’s artistic sensibilities as I had originally done.

The Shearer photograph had the same magnificent “presence” as the Rube de Remer “artist model” photograph. I could easily imagine Shearer posed and draped on a modeling throne in Johnston‘s studio. When I later acquired copies of Johnston’s art school records from the Art Students League of New York and the National Academy of Design, I found that he had indeed taken life classes with posed nude models. An historian at the National Academy told me that in those days students would paint from the nude in open north light studios all day long. Instructors walked through the studios and critiqued the young artist’s work. In addition, it was customary in the turn of the century art schools to have French academicians teach American artists the use of drapery. And after learning the techniques the students themselves draped models for the class to draw. Johnston must have learned the art of drapery well, and loved doing it, because it became his trademark.

I proceeded to begin a series of discussions with Christopher Sweet. We discussed the type of book Christopher was envisioning (a monograph), where to locate Johnston‘s work, the size of the book and number of photographs (200-250), the type of essay I would write(60 pages), a timetable for producing the book, and of course, a contract. We both agreed that it was going to be a magnificent art book. Everything seemed to be falling smoothly into place. I acted as my own agent. But it wasn’t long before I was regretting that I didn‘t have one.